April 15th, 2021 marks the 7th year since the Honourable Supreme Court of India passed the NALSA Judgement which laid down favourable guidelines for the transgender community in India. The National Legal Services Authority, which was established as a means to provide free legal services for the marginalized, underrepresented/unrepresented, and oppressed sections of the society, petitioned the Court to address the worrying issue of the danger and threat to the lives of trans persons. In addition to recognizing at the outset the trauma that transgender persons have to go through, the Judgement quoted many international developments to substantiate its claim for demanding accountability from the state and public both. The Judgement made references to the constitutional provisions of Article 14, Article 15, and Article 16 (Right to Equality), and Article 19 and Article 21 (Right to Freedom). Recognizing that “human rights are individual and have a definite linkage of human development, both sharing common vision and with a common purpose”, and referencing the spirit of the Constitution, the Honourable Court laid down a number of guidelines, one of the most significant one being the right of a transgender person to self-identification of their gender. According to this, no external authority would have the power to declare or not declare someone as a transgender person. The Judgement also called for reservations for trans persons as a tool of providing affirmative action. Further, governments are instructed under this Judgement to ensure a trans person’s dignity and address problems like medical insistence on surgery, non-sensitivity towards dysphoria, and social stigma.

The NALSA Judgement of 2014 seemed to positively impact the lives of transgender persons in India in a lot of ways. But the significant question remained – did these provisions prompt the state to undertake measures to ensure the benefits to trans people? And if yes, did these benefits even reach trans persons on the ground?

Despite the Judgement being passed in 2014, even 3 years later, in 2017, Vikalp’s meetings with state officials showed that they were unaware about the NALSA Judgement, despite being the primary implementer of the guidelines. Later that year, applications made to the government for name and gender change through the gazette were sent back citing a lack of surgery. This clearly violated the NALSA guidelines which held that medical intervention was not a necessary prerequisite for gender identification. Using the provisions of NALSA, we were also able to push medical authorities to perform gender affirming surgeries free of cost.

Even till 2018, Vikalp was still conducting sensitization and awareness trainings for government officials and lawyers alike, who although now had a sense of the Judgement, but still lacked clarity on the important provisions of self-identification and dignity of trans persons. It was largely our intervention which enabled the state government of Gujarat to acknowledge the presence of transgender men and include them in their understanding when they referred to the NALSA Judgement. With reference to NALSA, meets were also held with officials of the Education Departments, to discuss the integration of the provisions of NALSA in educational curriculums, and to delete outdated and oppressive “information” in medical and other textbooks. As a part of the VISTAARA project, sessions on NALSA, with officials as well as with stakeholders, continued to be held in 2019-2020, despite it being almost 5 years since the Judgement had been passed.

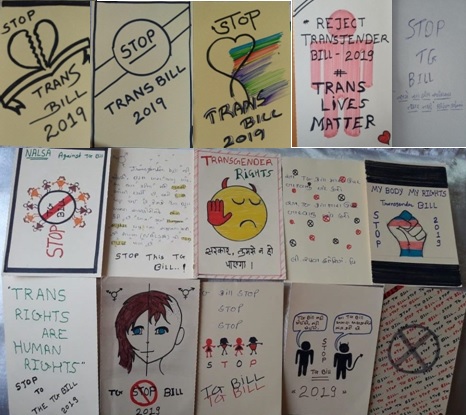

The Government of India had already passed two bills regarding transgender persons, one in 2014, and the other, a reworked version in 2016. Both of these bills were met with heavy criticism from transgender activists and persons alike, since both of these versions very clearly strayed away from the spirit of the NALSA Judgement. They took away the right of self-identification of trans persons, and called for a “screening” of a trans person’s gender. Subsequently, another Bill in 2019 was tabled and received the President’s assent in 2019 itself, making it the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019. But the question remains – after so many revisions and amendments, has this Act managed to live up to the spirit of NALSA?

The NALSA Judgement provided for reservations for transgender persons in educational and employment institutions, but neither the Act, nor the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Rules, 2020 make an effort to provide any affirmative action to the community. Further, the Act and Rules continue to go against the primary tenet of the Judgement – self identification – by requiring a trans person to make an application to the District Magistrate to be able to identify as “transgender”, and to undergo at least one form of medical intervention in order to be able to legally change their gender to a binary one (i.e. male or female). In essence, the state authority has to power to “accept” or “reject” a transgender person’s application for a change in name and gender. The Act further provides imprisonment for offences committed against transgender persons (including rape) for a term of 6 months to 2 years only, as opposed to the term of imprisonment for a rape-accused (of a cis woman), standing at 7 -10 years. The Act also does not recognize non-binary/genderqueer/genderfluid identities, and continues to ignore socio-cultural identities. A fundamental issue of accessibility when it comes to the passing of the Act is the fact that it is available only in English, and was passed when the COVID-19 pandemic was raging, leaving no option open for transgender persons and activists to be physically present together to demand from state officials their participation in consultancy.

The Trans Act does not exist in isolation; it is a product of prevailing social and cultural ideas and norms, and eventually, it is made by cisgender persons. The absence of participation of trans persons in the framing of any law for the protection of their own rights will do little to elevate their position, both socially and economically, for concerns raised on the basis of the lived experiences of trans persons in India have not found place in the Act or the Rules.

References:

- Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019

- Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Rules, 2020

- Section 375, Indian Penal Code

- Section 376, Indian Penal Code